How to Use Field Note Books

by M.D. Crisp & D.J. Cummings, January, 1977

(Updated by A.M. Lyne, September, 1996)

Table of Contents

- Aims

Service to Taxonomy

Service to Ecology

Service to Horticulture - Criteria

Simplicity

Computerisation

Interpretation - Data

Some Important Points in Data Gathering

- What to Record

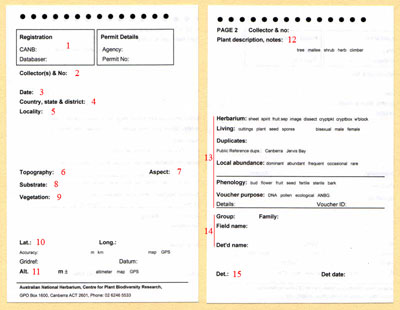

Click to enlarge to full size, red numbers refer to following textOne Page Per Collection

Registration Number

Collector and Number

Date

State and District

Locality

Topography

Aspect

Substrate

Vegetation

Latitude and Longitude

Altitude

Plant Description and Notes

Habit

Host Organism

Water Environment

Artificial Environment

Growth Form

Herbarium

Living

Duplicates

Abundance

Phenology

Voucher purpose

Name

Determined by - Some Final Comments on the Field Note Book

- References

- Herbarium Labels

Aims

Data collected without a specific purpose in mind is usually wasted. Hence before we consider what data should be collected during routine field work we must examine our aims.

The herbarium sheet carries all the data from the field collection. It also carries the original plant specimen; hence it is the ultimate reference point for all associated data, and for all purposes.

Herbarium specimens service a variety of purposes. These may be summarised conveniently in three categories:

Service to Taxonomy

The value of ecological data in practical taxonomy (i.e. describing and naming taxa) seems to be played down by most authors. However, there is no doubt that the majority of contemporary taxonomists do use ecological evidence in making decisions about taxa. This is strongly implied by Heywood (1973):

-

"It is a tenet of present-day taxonomy that species and sub-species are intended to be population units. ... For the general taxonomist a population is any group of individuals considered together at any time because of features they have in common. This tends to mean in practice a group of plants growing together which look similar, or a series of groups as they occur over a particular area or region."

In other words, a taxon is defined on both the morphological similarity and commonness of distribution of its individuals.

A common distribution implies a similarity of ecological factors within the population. From genetic and evolutionary theory, this must be so i.e. a population will not remain a population if the ecological factors, and therefore the selection pressures towards evolution, vary significantly within it.

Service to Ecology

The important role of taxonomy in providing names of the plants with which ecologists deal is obvious. The potential role of the herbarium specimen in providing data for ecological research is less obvious but also important. In a recent submission to ABRSIC the Ecological Society of Australia (per R.W. Johnson) made this quite clear:

-

"An important corollary of the taxonomic exercise lies in the collection and maintenance of specimens uniquely identified and adequately annotated, which can be used as an information source by other biologists. We consider that the value of the collections of specimens could be considerably enhanced by the addition of appropriate ecological information, provided that this information were in an acceptable and accessible form. While the particular information required may vary from taxon to taxon it can conveniently be summarised under six headings:

- Geographical location including altitude or depth.

- Physiography (topographic position) e.g. mountain top, sea shore, lake, sand dune, alluvial plain.

- Substrate e.g. parent rock, soil, building, lake bottom.

- Vegetation e.g. local dominant, species structure, community type.

- Medium (environment) e.g. water, litter.

- Method of collection e.g. plankton net, light trap.

Not all specimens would require complete enumeration of the six categories."

Service to Horticulture

In the Australian National Botanic Gardens the herbarium specimen and the living plant are so closely linked that it is logical to use the existing (or any future) information system to pass on ecological data from the field to the horticulturist. Such information is essential in determining the requirements of the living plants at all stages from propagation in the nursery to siting in the Gardens.

Criteria

Several considerations limit the types of data to be collected.

Simplicity

-

The data categories must be simple enough to be understood by people with no ecological training.

Computerisation

-

The data must be reducible to numbers for computerisation. This requires a strict classification of data and simple, logical terminology.

Interpretation

-

The data must be interpretable in themselves i.e. by reference to the herbarium sheet alone. This is because they will be used by outsiders to the Herbarium.

These considerations mean that we must adopt standard systems of ecological description with relatively simple and concise terminology. I shall now proceed to outline the proposed systems, to list the terminology, and to define the terms where necessary.

This system is intended to be all-inclusive. All descriptive terms which you will need should be in these notes. You must therefore attempt to express all your data in these terms and no others. If the particular situation is so unique that it is not covered by these notes, then you should describe it in the set categories to whatever extent you can using the given terms, and elaborate its peculiarities in the "Notes" section.

Data

Some Important Points in Data Gathering

I am proposing two levels (sometimes three) of detail for the data in most categories viz. a general and specific level. If you are unable to recognise the specific type then the general will suffice. If you are in any way uncertain of the specific category then you should record the general type only. This is most important - you must not give a misleading impression of the accuracy in your data. Always go from the general to the specific when you record data.

-

Example:

-

"Substrate : Rock, sandstone."

Rock is a general substrate type; sandstone is specific within that type.

In general you should aim to collect data on the immediate environment of the plant i.e. data which cannot be obtained from a map at a later date. The reason for this should be obvious. The principal exceptions are altitude, which is very important, and landscape, which places topography in its context.

-

Example:

-

"Topography : Hilly terrain with deep gullies and sharp crests."

is poor because this information would be apparent from a map, and tells you nothing of the immediate environment of the plant. A better description is "Topography : Hills, steep slope in gully."

Your field book should have only one entry per heading. Each entry should be expressed as a series of phrases, separated by commas, with a full-stop at the end of the entry. Each phase should correspond to one level of the general-to-specific sequence. This may seem pedantic, but reduces verbage and make interpretation of the data easier for somebody else.

-

Example:

-

Location: c. 50km NW from Griffith, Fred's Lagoon, 0.5km along W bank from S end.

Always use a soft pencil (HB or F) for field recording.

All measurements must be metric.

What to Record

For those who do not have one of our field note books, here is one of the pages. The red numbers below refer to the numbers on the example page. You can download a Word version too.

|

One Page Per Collection

Each page of your field book should be used for a single collection; no more, no less. A single collection is defined as material taken from one plant on a particular day. Thus an herbarium specimen, cuttings, and seeds, all taken from the same tree on 27 August 1976, comprise a single collection. A further specimen taken from the same tree a week later does not belong to that single collection, and must be treated separately. There are two exceptions to this rule. Very small plants, especially annual herbs, do not provide enough material for an herbarium specimen, let alone propagating material. In such a case several plants from a single localised population are regarded as a single collection. Whole-plant transplants may also be grouped with a voucher from another plant as a single collection.

Registration Number (1)

The space after the heading CANB is for the registration number of the specimen. This number is not to be entered in the book during the field trip, but will be added later when the field book is registered.

Collector and Number (Coll.) (2)

Write you name and your personal collecting number in this category. Your name must have all initials, and your surname in full. Ideally you should have only a single number series, starting from 1 increasing throughout your collecting career. In the event that you lose your field book, or leave it behind on a trip, leave a good gap from what you think the last number was and recommence your number series from a much higher number. A gap is infinitely preferable to duplicated numbers. More complex number series usually causes confusion. When you write your number on the tags attached to the specimens, always precede it with your full initials, e.g. MDC 2567. Most people are not handwriting experts, and the tag is often the only means of tracing a specimen to its field book. Always assign exactly one number, no more or less, to each collection. If other collectors have assisted you, list their names after your number. Acknowledgement of assistance is only a common courtesy, and the days of solitary collectors are mostly over.

-

Examples:

- F.E. Davies 1279 (tag - FED 1279)

- I.R. Telford 4750, M.D. Crisp & A. Tyrrel. (Tag - IRT 4750)

Date (3)

The date is always the date of collection. The standard way of expressing it is thus : 19 JAN 1996, i.e. with numbers for day and year, and three letters, upper case, for the month.

State and District (4)

The state in which the collection is made should be indicated by one of the standard symbols:

-

WA - Western Australia

NT - Northern Territory

SA - South Australia

QLD - Queensland

NSW - New South Wales (including Jervis Bay)

ACT - Australian Capital Territory

VIC - Victoria

TAS - Tasmania

- Oceanic Islands

Each state has been divided into a number of districts for the purpose of field work planning and simplifying locality descriptions. The districts are based upon those already used by herbaria in their respective states. Districts have been defined according to convenience of access combined with geographic and ecological uniformity. A large master map in the herbarium shows the district boundaries in detail, and is your primary source of reference.

A listing of state botanical districts is here

In your field book you should indicate the district by the standard two letters (lower case), as indicated in the above linked document.

Locality (LOC) (5)

The precise collecting locality must be recorded, preferably to the nearest 1/10th kilometer (km), or at the worst the nearest lkm, from a precise and well-known map-point. If the place is remote, its relationship to a better-known place should be given. Map names are acceptable, local names are not. Suitable reference points are post-offices (usually at the centres of towns or cities), trig-points, road crossings or junctions and river or stream junctions.

If your distance measurement is a road kilometerage you must use the words "x km from A along rd to B". If the distance is measured in a straight line, not along roads, the direction, preferably as a bearing in degrees(0) from true north, must be stated. For accuracy, avoid distances of more than 20km. Always follow a general-to-particular sequence.

Use only metric measurements.

Some abbreviations are acceptable by virtue of being well-known and unambiguous, and are listed below. All others are either poorly known or may be confused. Words not to be abbreviated are also listed below.

Examples:

-

Stirling Range, 1.3 km 154° from Ellen Peak.

Budawang Range, Endrick River, 2.5 km upstream from junction with Shoalhaven River, left bank.

15.4 km from Braidwood along road to Nerriga. (It is assumed that the distance was measured from Braidwood P.O.).

c. 60km NNW from Balranald, 8km from Bidura h.s. along rd to Wampo Stn.

Acceptable Abbreviations:

-

km - Kilometre(s)

c. or ca. - Approximately (circa)

rd - Road

Hwy - Highway

Rly - Railway

Rly Stn - Railway Station

Stn - Station (grazing property)

h.s. - Homestead, head station

P.O. - Post Office

Mt(s) - Mountain(s), mount

Ck - Creek

Is. - Island

Penin. - Peninsula

Words not to be abbreviated:

-

Range, River

Park, Peak

Port, Point

Cape

State Forest

Junction

Lake

Waterhole

Topography (6)

Details of topography recorded when collecting plants gives botanists, ecologists and horticulturists a general insight into the ecosystem to which the plant is adapted.

There are three levels of detail necessary to adequately record topography - Landscape, Landform and Position on Landform.

- Landscape

This is a description of general topography of a region; it can be determined from a map but it is useful to enter it in the field to place specific topography in context.

- Coastline - Land adjacent to the sea

- Plain - Level land of low altitude

- Undulating land - Rolling land with slopes up to 8 degrees

- Hills - Slopes in range 8 to 20 degrees

- Mountains - Higher and generally steeper than hills

- Plateaux - Elevated plains

- Coastline - Land adjacent to the sea

- Landform

This is a description of the more localised features of an area. It is expressed by type (a noun) and in most cases a qualifier (an adjective or descriptive phrase). The qualifier can nominate magnitude or simply add further description. Magnitude should be specified as often as possible, e.g. size for depressions and rises; degrees of slope; size of river; etc. Further descriptive qualifiers should be added as required, e.g. eroded slope, rocky outcrop, isolated hill.

Landform varies considerably and is not easy to categorise; however, the following set of terms when used with qualifiers should give adequate coverage for our needs.

The following listing of landforms is also available here

- Depressions - Valley, gorge, gully, crevice, depression, gilgai, sinkhole.

- Rises - Peak, rise, ridge, spur, mesa, butte, knoll, volcanic plug, hill, outcrop, dunefield, mine dumps, artificial fill areas, roadside embankment, railway embankment, channel embankment.

- Slopes - Escarpment, cliff, scree, alluvial fan,slope - when specifying slopes indicate the degree of rise, viz:

-

gentle - to 2 degrees

moderate - to 50 degrees

steep - to 150 degrees

very steep - above 15 degrees

- Artificial slopes - roadside cutting, railway cutting.

- Flats - Desert, hardpan, pavement, floodplain, riverflat, river terrace, creek flat.

- Waterways - River, stream, creek, braided stream, spring, channel.

- Waterbodies - Lake, lagoon, billabong, swamp, marsh, bog, seepage area, reservoir.

- Coastal -

-

Bay, cove, inlet.

Island

Tidal channel, tidal flat

Estuary

Coastal cliff, coastal hill

Coastal dune, coastal foredune, coastal strand, headland.

- Depressions - Valley, gorge, gully, crevice, depression, gilgai, sinkhole.

- Position on Landform

Gives the specific location of the specimen and is a further qualifier.

-

Examples:

-

100m up 200m vertical cliff

edge of stream

upper steep slope

mid point of steep spur

Aspect (7)

The direction in which any piece of land is sloping gives valuable information on micro-climatic conditions on that slope - especially in relation to the amount of sunlight received. Aspect should therefore be specified to the nearest 45 degrees, i.e. N, NE, E, SE, S, SW, W and NW.

Substrate (8)

Substrate is that medium in which a plant is fixed. In most cases it will be soil but can also be rock, mud, host organism, water or artificial material.

- Rock

The type of rock underlying an area will have a significant influence on the general environment of that area. For example, the occurrence of resistant granite to the W of Canberra has resulted in the formation of the Brindabellas, and the basalt flows of the Western District of Victoria have produced vast plains with highly fertile soils. Thus, the recording of rock type will give useful information on land characteristics and enable the building up of a complete picture of plant environment.

Rock type should be recorded in as much detail as the collector feels competent to give. The following table is also available here.

The specific type should not be given if the collector is not confident of identification, although it is acceptable to put basalt-like, partly metamorphosed sandstone and so on. Consulting a geologic map (located in the herbarium) either before or after a field trip is good for assisting or confirming field identification.

- Soil

Reliable information on the characteristics of a soil in which a certain plant is growing is essential for successful propagation and cultivation of that plant. It is a little difficult to collect, as soil morphology and soil classification are complex. A further difficulty to the plant collector is that most of the soil is underground and difficult to study. Therefore most of the data collected will pertain only to the surface soil, although, not to be disheartened, the information available from surface soil characteristics will often be sufficient to aid propagation and planting out.

The following table gives a relatively simple method of describing the surface soil when collecting plants. By choosing a word or phrase from each column a description of the soil can be built up.

The following table is also available here.

Examples:

For rainforest soil - deeply littered, well-structured black loam.

For soil behind the Herbarium at the ANBG - stony, moderate-structured pale-brown clay-loam.

The rock of the area can and should be mentioned in this description by adding a suffix phrase; e.g.

... on graniodiorite

... on mudstone

Definitions

Skeletal soil - One dominated by skeleton of parent rock. Stony and shallow.

Soil structure - Describes the manner in which soil particles are assembled in aggregate form. A well-structured soil is friable and well-drained with obvious peds. A poorly-structured soil is tough and poorly-drained without obvious peds.

Organic soil - Soil dominated by organic matter (20%). A fluffy, loose and very light soil.

Mud - Accumulation of fine soil particles in a wet situation such as a swamp, stream bottom or river estuary.

Ped - Naturally cohering unit of soil

Host Organism

Parasite - Record type of host and position on host. Give details of host's substrate.

Epiphyte - Record whether aerial or terrestrial. Record type of host and position on host. Give details of host's substrate.

Water Environment

Inland aquatic - Submerged plants fixed to bottom of stream or lake. Record type of surface to which attached i.e. mud, sand or rock. Record rate of movement of water and degree of salinity.

Marine - Submerged plants, attached below high water mark. Record type of surface to which attached.

Free floating - Record whether at or below surface, inland aquatic or marine. Record rate of movement of water and degree of salinity.

Artificial Environment

Record type of surface, e.g. -brick wall, fence post, mine dump, concrete, etc.

Vegetation (9)

Two variables are to be recorded, namely structure and dominants.

- Structure

Structure is determined from the life-form, height and density of the tallest stratum or level in the vegetation. Australian structural types are defined and named in the table below, taken from Specht (1970).

The following table can also be found here.

Notes on the table

- Isolated emergent trees may project from the canopy Of some communities. In some cases closed-forests, emergent Araucaria, Acacia or species may be so frequent that the resultant structural form may be better classified as an open-forest. Many so-called "wet sclerophyll forests" fall into this category.

- Similarly, scattered trees and shrubs may be regarded as emergents in predominantly grassland, heath or shrubland formations ("very sparse" column).

- The distinction, or lack of it, between trees and shrubs is discussed under Habit.

Disturbed vegetation

Much of Australia's vegetation has been altered from its original state, even to the extent of being completely replaced by new vegetation. If you recognise the type of disturbance, describe it in your field book by using one of the following terms as a prefix to the structural term.

General terms -

Regenerating after a disturbance (name the type of disturbance).

Secondary (means vegetation permanently altered from its original state e.g. shrubland converted to secondary grassland by sheep grazing).

Specific terms -

Logged, grazed, overgrazed, burned, recently burned, cleared, partly cleared, wind-thrown, inundated, diseased (name disease or insect if possible), droughted.

Artificial vegetation - (always in an artificial landform)

Crop, planted forest, parkland, garden(s), lawn, weed community. The "dominant" species of these vegetation types should be named just as for natural vegetation, if possible.

- Dominants

One or two dominants in the tallest, and perhaps one or two from the principal lower, stratum should be named. Great care must be taken in selecting the dominants. Often the most conspicuous species is not the most common (and therefore dominant) but may appear so.

You will observe that the traditional descriptive terms such as "dry sclerophyll forest", "wet sclerophyll forest", "rainforest", etc. do not appear in this scheme. They are unsuitable for formal vegetation description because they indicate little about the detailed structure of the community. They also make unnecessary and misleading implications about the moisture relations of the community. In general you should avoid describing the moisture conditions. It is very difficult to subjectively make an accurate assessment of them in the field. In any case they can be assessed reasonably knowing the rainfall (from a map) and the other habitat factors.

Latitude (Lat.) and Longitude (Long.): (10)

Herbaria express localities in latitude and longitude coordinates as well as descriptively. This enables people unfamiliar with the region to place the locality on a small-scale map. It also allows more direct comparisons between localities.

Give coordinates to the nearest second (if you used a GPS (global positioning system) unit) or to the nearest minute (if you did not use a GPS unit). They can be obtained from a GPS unit or by pinpointing the locality on a map with 1 : 250,000 scale or better, and measuring the coordinates from the map margins. All latitudes in Australia are in degrees and minutes s (i.e. S of the equator) and all longitudes in degrees and minutes E (i.e. E of Greenwich).

-

Example:

-

Lat.: 35° 26' 43'' S Long.: 135° 17' 29'' E

Altitude (11)

Give altitude in metres (m). Precision should preferably be to the nearest 10 m, but in very mountainous country the nearest 50 m will do. For near-coastal situations, it may be necessary to go to the nearest 1 m. Altitude can be estimated from good topographic maps with contours. Do not record the altitude reading given by a GPS unit - they are invariably erroneous.

Habit (= Plant description, notes) (12)

When describing habit you should indicate growth form with a qualifier and size. Describe only those features which cannot be seen on the herbarium specimen, or are distorted by pressing.

The following list is also available here.

Growth Form

Tree - a tree is a woody plant, usually with less than 3 stems and more than 5m tall.

Shrub - a shrub is a woody plant, usually with more than l stem and less than 8m tall. A shrub usually has its principal branching point at or near soil-level.

Mallee - a eucalypt with many (often tall) branches arising from a massive underground stem or lignotuber.

Sub-shrub - shrub-like but the stems are herbaceous in their upper parts, and die back away during adverse conditions. Sub-shrubs are usually decumbent or procumbent but may be erect e.g. Haloragis. They often have tufted stems and a lignotuber-like root-stock e.g. Daimpiera.

Herb - no woody tissue present.

Fern - any pteridophyte.

Parasite - a terrestrial parasite is a tree or shrub or herb. An aerial one requires mention of the word parasite for clarity as the terms 'shrub' etc. are inappropriate.

Vine or liana (liane) - a climber rooted in the ground.

Grass, sedge, rush, graminoid - these may be qualified by 'tussock-' or 'tufted'.

Arborescent shrub/grass/herb, bamboo.

Rosette tree - unbranched stem with crown of leaves, e.g. palms, cycads, Xanthorrhoea, tree ferns.

Rosette shrub - e.g. Dianella.

Stem-succulent shrub - rare, e.g. Sarcostemma, Opuntia and some Euphorbia species.

Hummock grass - Triodia and Plectrachne.

Mat plant, cushion plant - found in alpine areas.

Qualifier

An enormous variety of qualifiers have been used to describe habit. However, the fairly limited list below should cover all possibilities, and you should limit yourself to using these terms.

Terms

Clonal, thicket-forming.

Straight, crooked, slender, robust, whipstick, virgate.

Open, dense, diffuse.

Many-/few-/long-/short- stemmed.

Divaricate/flexuose /drooping/erect/spreading/ whorled/ intricate/ arching stems, branches or branchlets.

Much-/few- branched.

Erect, leaning, decumbent, procumbent, prostrate,ascending, pendulous.

Weak, trailing, straggling.

Pyramidal/cylindrical/rounded/umbrella-shaped/ spreading/weeping crown.

Tufted, tussock.

Creeping/shortly creeping/extensively creeping/ insidiously creeping, rhizome, rhizomatous, rooting at nodes.

Definitions

Virgate - twiggy (and usually also slender).

Divaricate - branching or spreading widely or at right angles.

Flexuose - zig zag.

Intricate - closely interwoven (divaricate plants are usually also intricate, unless branching is only in one plane).

Decumbent - more or less horizontal with down-turned tips.

Procumbent - more or less horizontal with up-turned tips.

Prostrate - completely flat on the substrate. Procumbent and decumbent plants are often incorrectly termed prostrate.

Ascending - weakly erect.

Size

Always record height unless a whole plant is taken as a voucher. If no other measurements are recorded the suffix "tall" or "high" is unnecessary. If you also record breadth, diameter at breast height (dbh) or other measurements (but only if they are remarkable), then you must write "tall", "broad", "dbh", etc.

Examples:

Straight tree, long-stemmed, spreading crown, 25m tall, lm dbh.

Fern, shortly creeping rhizome, 70cm.

Pendulous woody parasite, 2m.

Dense tufted herb. (Height is apparent from the specimen.).

Decumbent open shrub, 40cm tall x 200cm broad.

Sedge, dense tussock, lm.

Notes

This section is reserved primarily for addition of features of the plant which either are not present on the specimen or may be lost during processing and preservation. This applies particularly to bark-types and flower colour.

Anything at all about the specimen which is noteworthy but not covered in the given categories should also be mentioned here e.g. "Female plant is MDC 2167", etc.

Type of material, abundance and duplicates (13)

Herbarium

The type of material that makes up the collection, circle the relevant item/s:

- sheet – pressed plant specimen (one should always be collected).

- spirit – flowers etc. that have been put in 70% alcohol.

- fruit sep. – bulky fruits destined for the carpological collection

- image – photographs/digital images of living plant, if more than one write image name

- dissect – floral card with dissected floral parts, e.g. orchids

- cryptpkt – specimens to be filed vertically in envelopes, usually mosses, liverworts and lichens

- cryptbox – bulky cryptogam specimens that require protection in a box, e.g. fungal fruiting bodies

- w’block – wood and bark sample

Living

Information about material taken to propagate at ANBG, circle the relevant item/s:

Cuttings, plant, seed, spores, bisexual, male, female

Duplicates

The number of duplicate herbarium specimens intended for distribution to other herbaria and the code for each herbarium (see Index Herbariorum for codes) or leave for herbarium staff to decide.

Public Reference dups.: Canberra, Jervis Bay – Public Reference herbaria administered by CANB

Abundance

Abundance is an expression of the commonness or otherwise of a population (or species) in the vegetation in which it is found. In your field book, it is the abundance of the population which your specimen represents which you must record.

Abundance is not a simple concept, and many measurements have been devised to represent it. Some are density (or number), frequency, cover, volume and weight. Weight (or biomass) is the most generally accepted, and volume is a fair approximation to it.

You should estimate the abundance of the population from which your specimen is taken from its weight or volume, by taking careful account of the following points.

- Abundance must be estimated as a relative term in relation to the layer of the vegetation in which the plant occurs. Thus the abundance of a tree species is relative to that of the other tree species, that of a shrub species to that of the other shrub species, etc.

- Many species do not have random or regular distributions, but are clumped in varying degrees. If clumping is apparent in the population, you must record the fact (see terminology below).

-

Four types of population dispersion in a community.

A - Random dispersion (note its apparent irregularity)

B - Clumped or contagious distribution.

C - Regular or negatively contagious distribution.

D - Combination of strong clumping of individuals into colonies and regular distribution of the colonies as wholes.

Species which are clumped usually appear to be less abundant than they really are. Take this into account and make your judgments carefully.

- Bias may occur when a species is either more or less conspicuous than the rest of the vegetation. For example, a broad-leaved tree with large bright flowers in full bloom will look far more common than it really is. Conversely, a leafless diffuse scrambler will be all but invisible, even if it is very common. Again, use your judgement carefully to avoid bias.

Terminology

- small, medium, large, or extensive clumps or in,

- clumps or strong clumps.

- Dominant in strong, extensive clumps.

- Rare.

- Frequent in clumps

-

Abundance - dominant, common, frequent, occasional, rare.

(Note that a dominant species is one of the most abundant 2 or 3 in its layer).

Clumping (if present) can be in -

Phenology

The reproductive and vegetative state of the specimen collected, circle relevant states:

Bud , flower, fruit, seed, fertile, sterile, bark

Voucher purpose

Often the material is collected for a specific purpose, circle purpose/s if appropriate:

- DNA, pollen, ecological, ANBG

- Details: details or name of project

- Voucher ID: if the voucher will have a different number to the herbarium accession number allocated to the collection when it is databased.

Name (14)

Four levels are provided for recording the name and taxonomic position of the specimen viz. Group, Family, Field name and Determined name. The first three of these categories are to be recorded as far as possible in the field.

- Group

The higher order taxonomic level to which the specimen belongs. The higher order taxonomic groups are here.

- Family

Every flora handbook and every herbarium differs slightly in its family concepts. Therefore you should familiarise yourself with this institution's concepts and usage. The herbarium card index lists the families of genera in our collection, and many which are not.

- Field name

Enter the botanical name of the specimen, as far is known.

- Determined name

The Determined name is determined by the botanist in the herbarium, and is not to be recorded in the field, even by a botanist.

Determined by (Det.) (15)

When Determined Name is entered (later, of course, not in the field), you should write the name (initial and surname) of the botanist who made the determination, followed by the date of determination.

Some Final Comments on the Field Note Book

If in doubt, record more general terminology, rather than erroneous information.

When more than one collection is made at a given locality, much of the data may be repeated from one page to the next. Indicate repetition by leaving the given category blank.

Make sure that you fill out every page in your book fully. Remember that blanks are interpreted as repetition.

If for some reason you are unable to record the data for a given category, although the category is relevant, enter "ND" for "no data".

If a category is irrelevant in the given locality, e.g. aspect in a flat landscape, enter "NA" for "not applicable".

If you think you have a situation which cannot be described by these terms in these notes, think again. Perhaps it can be described by some of the simpler, less general terms. If the situation is unique, and this can only occur rarely, describe it in your own terms in the Notes category.

Always go from the general to the specific.

References

Heywood, V.H. (1973). Ecological data in practical taxonomy. In: Heywood, V.H. (ed.): "Taxonomy and Ecology." pp. 329-348. Academic Press, (London).

Ecological Society of Australia (1975). Submission by ESA to ABRSIC on taxonomic and ecological research in Australia. Bull. Ecol. Soc. Aust. 5: 1-4.

Specht, R.L. (1970). Vegetation. In: Leeper, G.W. (ed.): "The Australian Environment." pp. 44-67. CSIRO, (Melbourne).

Herbarium Labels

It is standard practice in Australia herbaria for the collector to write up their own field note book labels and to then pass the data on to a databaser. Once the draft labels have been produced from the database, it is the responsibility of the collector to thoroughly check them for accuracy. This is because only they can satisfactorily interpret their own field note book data, tidy it up, and correct any errors. Having made any neccessary corrections to the draft labels, these are then passed to the databaser once again for the production of final labels. If you do not feel inclined to follow your collecting through to this extent, you should not collect. See a botanist if you are unsure about any aspect of producing labels.

Instructions Concerning Herbarium Labels

- Herbarium labels are the authentication of a specimen which has usually been very costly to collect both in time and money. The facts recorded on the label should be accurate and complete so that it will stand alone as a self-explanatory document. An inaccurate or incomplete label is wasted information and can cause much time to be spent in checking details.

- It is the responsibility of the collector to provide accurate, complete information for the production of herbarium labels.

- Labels should only be produced through the database. Hand written labels are no longer acceptable.

- All labels must be originals. Photo copies are not acceptable.

- As accuracy is the keynote, meticulous care is needed both in giving the information and in databasing it. The labels should also be neatly arranged. Our labels go to interstate and overseas herbaria and we are judged by their appearance.

- Never write "E" for Eucalyptus in a name on a label. The "E" could stand for many other genera. We are all familiar with this as a short cut, but others are not always so.

- Also, in notes, use Euc. instead of E., for the same reason as above.

- Dates, by convention among all Australia herbaria, should be given as follows:- 12 DEC 1994, 12 JUN 1994, 12 SEP 1994. No full-stop is used after the three-letter abbreviations for the month.

- It is the responsibility of the databaser to refer the label back to the collector if information is not clear or not in conformity with these instructions.

- Author citation should be checked as to correctness. Special attention should be paid to punctuation which indicates abbreviated names. All author abbreviations are standard, and should be checked against the Australian Plant Name Index.

- Data should be given in the same sequence as in your field book. It must be written in full.

- Always give the State or Territory, in full, viz. "New South Wales" for "N". Always give the district in full, viz. "Southern tablelands" for "st". Add the word "district" for the following states only: Western Australia, Northern Territory, South Australia, and Queensland.

- Latitude and longitude figures should be put into the collecting book as soon as possible, preferably in the field.

- The name(s) of the collector(s) should be accurate, using the correct initials and full surname(s).

- Altitude should be given in metres.

- The collector should use one series of numbers throughout their career and these should be simple, perhaps with his/her initials as a prefix. Complicated systems should not be used.

- The name of the person determining the specimens should be given in full, even if it is the same name as the collector. Many specimens exist in herbaria where the collector or determiner is unknown because only initials were used.

- It is the resonsibility of the collector to ensure accuracy at the beginning and to check the final label.

![An Australian Government Initiative [logo]](/images/austgovt_canbr_90px.gif)